Sustainability in finance has moved from a niche concern to a central pillar of modern financial systems. What began as ethical investing has evolved into a broad framework shaping capital allocation, risk management, regulation, and long-term value creation.

Today, sustainability is no longer optional. It influences how banks lend, how investors assess companies, and how regulators define financial stability.

What sustainability in finance really means

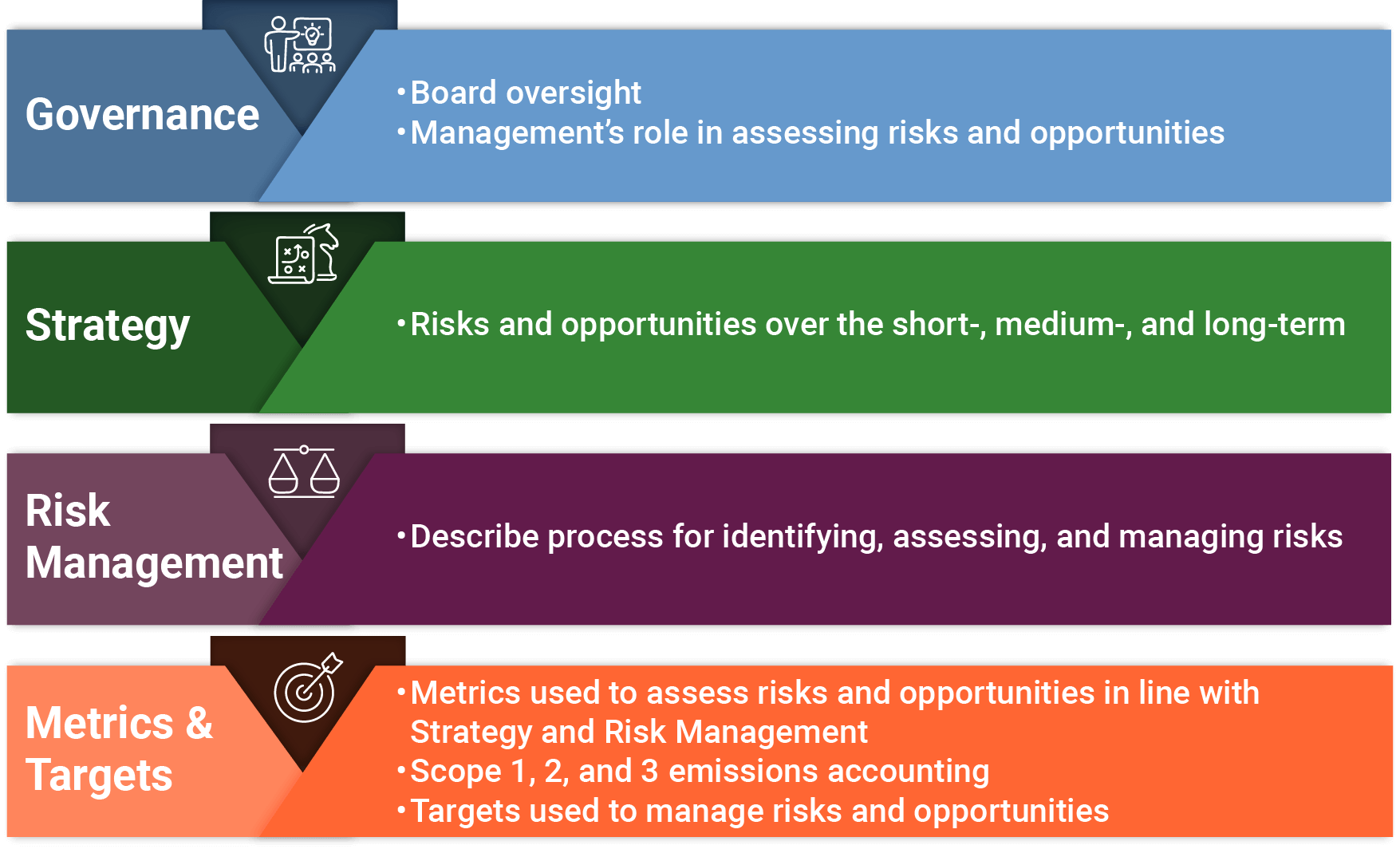

At its core, sustainability in finance refers to integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into financial decision-making. These factors affect risk, performance, and resilience over time.

Environmental considerations include climate change, resource use, and biodiversity. Social factors cover labour practices, inclusion, and community impact. Governance relates to transparency, accountability, and decision-making structures.

Rather than replacing financial returns, sustainability reframes how returns are achieved and sustained.

Why sustainability matters to financial systems

Financial systems depend on long-term stability. Climate risks, social inequality, and governance failures can all undermine that stability.

Physical risks, such as extreme weather events, damage assets and disrupt supply chains. Transition risks arise when economies shift towards low-carbon models, affecting valuations in energy, transport, and industry.

Social instability also carries financial consequences. Inequality, weak labour standards, and poor consumer protection can increase default risk and political pressure.

Governance failures often sit at the root of financial crises. Weak oversight and misaligned incentives amplify shocks rather than absorbing them.

As a result, sustainability is now treated as a systemic issue, not a moral preference.

The role of regulators and central banks

Public authorities play a growing role in embedding sustainability into finance. Central banks and supervisors increasingly view climate and ESG risks as prudential concerns.

Institutions such as the European Central Bank assess climate risks in stress tests and supervisory reviews. These exercises examine how banks would perform under different transition and physical risk scenarios.

At a global level, the Bank for International Settlements coordinates research on climate-related financial risks, helping align supervisory approaches across jurisdictions.

Regulation also shapes disclosure. Standardised sustainability reporting improves comparability and reduces greenwashing. Clear rules support market discipline by allowing investors to price risk more accurately.

Sustainable finance instruments

Sustainability in finance is reflected in a growing range of financial products.

Green bonds finance projects with environmental benefits, such as renewable energy or energy efficiency. Social bonds focus on housing, healthcare, and education. Sustainability-linked loans tie pricing to performance against ESG targets.

Impact investing goes further by explicitly targeting measurable social or environmental outcomes alongside financial returns.

These instruments channel capital towards long-term objectives while maintaining financial discipline. Their credibility depends on transparency, verification, and clear metrics.

ESG data and measurement challenges

Data sits at the centre of sustainable finance, but it remains imperfect. ESG metrics vary widely across providers, creating inconsistency and confusion.

Environmental data often relies on estimates and forward-looking assumptions. Social indicators can be context-dependent and difficult to quantify. Governance metrics require judgement rather than simple calculation.

Artificial intelligence and advanced analytics increasingly support ESG assessment. However, models are only as strong as the data and assumptions behind them.

Improving data quality and comparability remains one of the most important challenges for the sector.

Sustainability and corporate strategy

For companies, sustainability is no longer just a reporting exercise. It influences access to capital, cost of funding, and investor confidence.

Firms with credible transition plans often benefit from lower risk premiums. Those exposed to unmanaged ESG risks face higher scrutiny and potential capital constraints.

This shift pushes sustainability into boardrooms and executive decision-making. Finance teams now work closely with operations, strategy, and risk functions.

The link between sustainability and long-term competitiveness is becoming clearer, particularly in capital-intensive sectors.

The global policy dimension

Sustainable finance also reflects broader policy objectives. International agreements such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals provide a shared reference point for governments and markets.

Public finance institutions use guarantees, blended finance, and taxonomies to guide private capital towards priority areas. Alignment between public goals and private incentives remains critical.

Without coordination, sustainability standards risk fragmentation. With it, markets gain clarity and scale.

What sustainability in finance means going forward

Sustainability will continue to reshape finance, not as a trend but as a structural shift.

Risk assessment will increasingly incorporate climate and social scenarios. Capital will flow towards resilient and adaptive business models. Regulation will continue to tighten around disclosure and governance.

The challenge lies in execution. Frameworks, data, and incentives must align to avoid superficial compliance.

Sustainability in finance ultimately concerns how financial systems support long-term economic value. When done well, it strengthens stability, trust, and growth. When done poorly, it adds complexity without impact.

The next phase will determine which path prevails.